Fulbright in Ireland – The One-Month Mark

/After about a month in a new country, it becomes harder to respond to questions with “we just arrived.” So as my family and I have crossed over that imaginary yet noticeable line between tourist on holiday and (temporary) resident, it seemed like the right time to reflect. With that in mind, here are five things I think about Ireland:

First, a month is nothing. What becomes more pronounced each day is how much I still have to learn about Ireland, its history, its people, and its cultural tapestry.

Second, winter is highly underrated. Most people typically visit places when it’s warm. There’s a reason why tourists seem to be everywhere in the summer. But if you never visit Ireland in winter, you are missing something. The winter light, especially in the morning, is beautiful, with a softness that is best left to poets to describe. And the lack of tourists has given us even more opportunity to connect with the community. Joseph Brodsky used to spend winters in Venice. I get it now.

Third, we love cliff walks. Okay, full disclosure, we’ve done only one so far (Ballycotton), and we got caught in a ten-minute hail storm, but other than that, it was sunny the whole time. And amazing! The cliff walk was a wonderful muddy adventure, and the ocean alongside us as we walked was majestic.

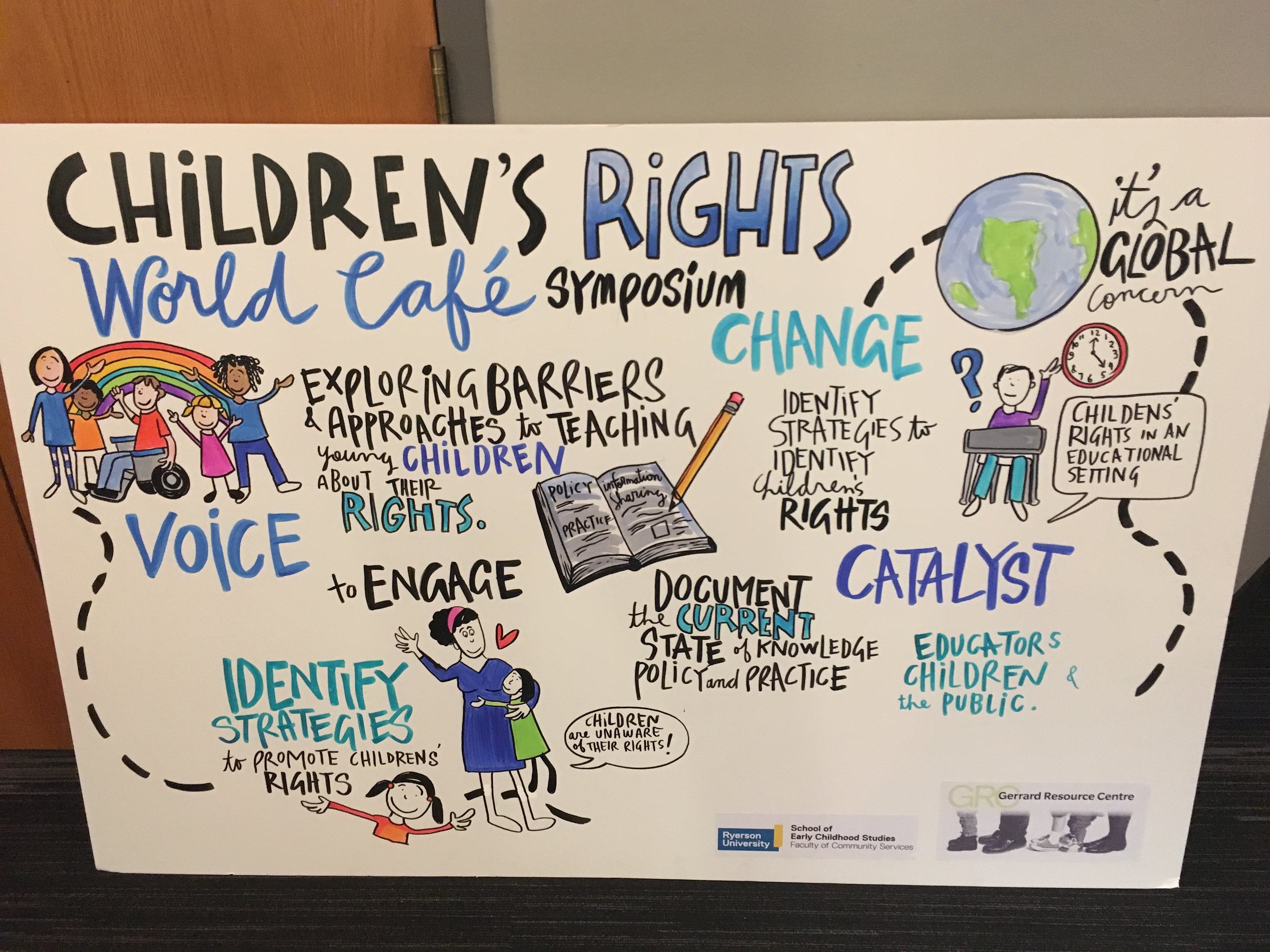

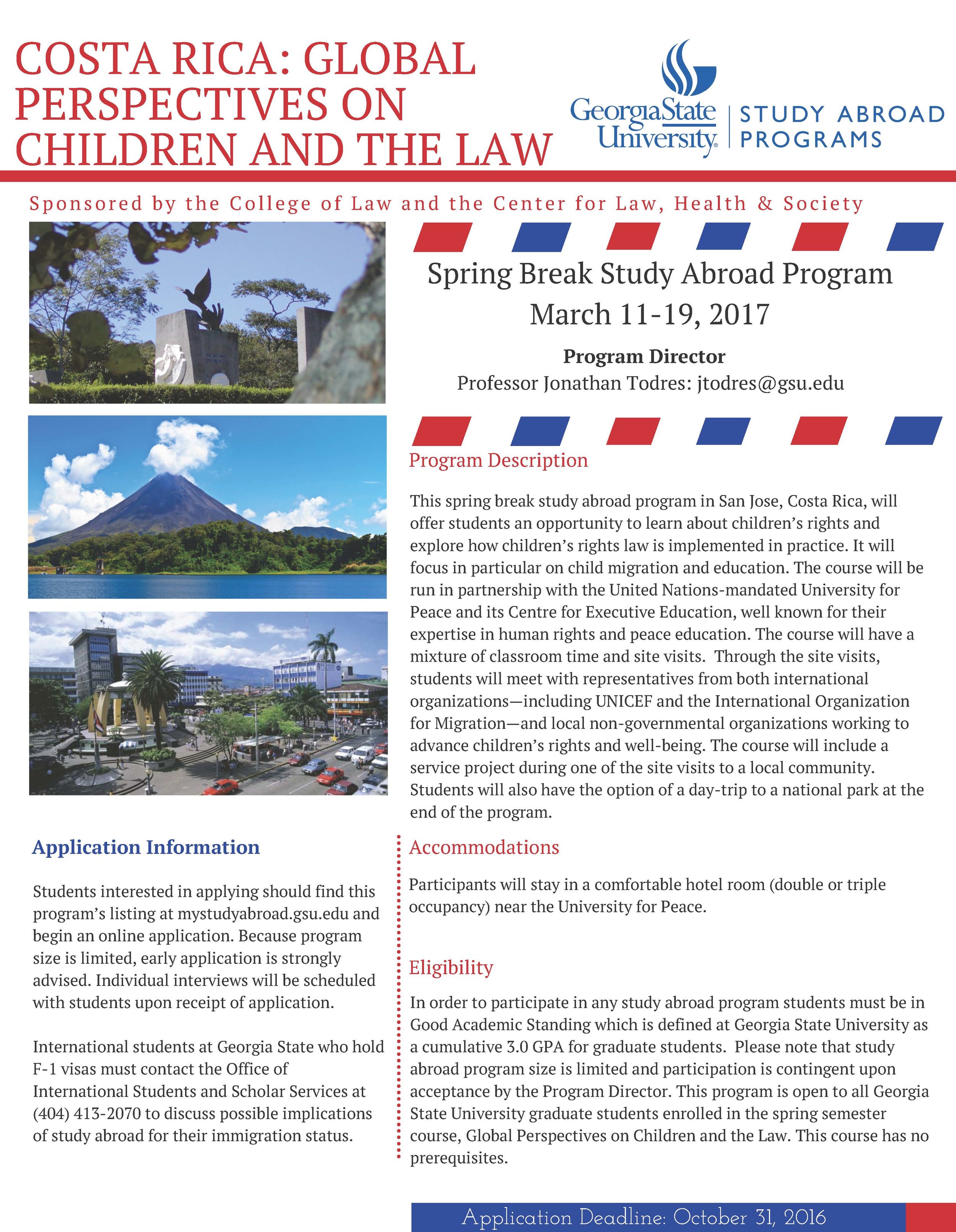

Fourth, on the work front, the Fulbright experience is an extraordinary opportunity. As researchers, we too often focus on, or succumb to the pressure of, producing the next publication. Make no mistake, I know I’m expected to keep producing while I’m on my Fulbright (and some might argue, produce even more). But the real gift of a Fulbright is the opportunity to slow down, to read, to make connections, and to reimagine one’s work and all its possible paths. As a child rights advocate/scholar, in just a few weeks, I’ve connected with partners in children’s rights, family law, human rights, social science, child development, public health, literature, and the arts, not to mention extraordinary individuals who work directly with children and youth in the community. All of this has inspired me to consider a range of projects and ideas for collaboration (some crazier than others). Regardless of which ideas go forward and when, this experience will shape my work for years to come.

Finally, in terms of lasting impressions, nothing surpasses the kindness of the people of Ireland. Everyone we have encountered has been so welcoming. I’ve lost count of the many moments of kindness – with colleagues, community advocates, school teachers and parents at our sons’ schools, employees at pubs and restaurants, bus drivers, and random strangers on the street. A couple Sundays ago, my wife, children, and I were wandering around the UCC campus in the late afternoon. We were in one building looking at an exhibit, when a security guard informed us the building was closing. However, when he learned we were new to Cork, instead of directing us to the door, he insisted on giving us a quick tour of a beautiful, historic room that we otherwise would have missed. That small but significant gesture epitomizes the kindness and generosity we’ve encountered everywhere. Our heartfelt thanks to him and to everyone who has made our family feel welcome. Certain places have reputations for being amazing in particular ways. Often the reality doesn’t live up to the hype. But not here. “Irish people are so friendly” we heard many times before we arrived. The reality far surpasses that. Even on grey days, everyone we meet is warm and welcoming. We feel very fortunate to be here.